The year of systems change: 3 things we need to do before we start

I stepped out of last year feeling dazed by the daunting problems we have to deal with in 2019 – especially, when reflecting on my own sphere of influence. Snowflake++SnowflakeThe term snowflake has been used to refer to young adults living in the ’10s, allegedly raised to be emotionally sensitive and to have an inflated sense of their own uniqueness and influence on the world. Read more allegations aside, as argued in my opinion piece last summer, I observe a fundamental flaw in how the industry of social innovation++Industry of social innovationFor social innovation I use the definition coined by the TRANSIT programme: a process of introducing new social relations, involving the spread of new knowledge and new practices (in which ‘new’ is a matter of degree and perspective’). frames social change. Complex problems are all too often ‘dumbed down’ to measurable ‘Key Performance Indicators’. It appears to me that systems thinking provides an opportunity to navigate this complexity, however, we do need to bear in mind three important preconditions.

Much of the current thinking about how to counter unwanted social outcomes, from youth unemployment to digital inequality, is based on the idea of how start-ups prototype, grow and scale their products. Eventually, ‘disruptive innovation’ can change the world as companies like Uber or Amazon supposedly did++Uber and AmazonI mention the word supposedly – arguably despite their technological innovations, they exacerbated existing inequalities and power relations through their extractive corporate model. Read more. In my work for institutions such as the European Commission this often seems the dominant frame of innovation.

I argue, however, that expecting one brilliant idea to save us from social ills through providing a direct service or product, obscures the complexity which underlies our society, including factors such as market design, institutions, information flows, power play and most importantly, values. Our current-day problems cannot be fixed by simple technical interventions, think of issues such as climate change, inequality, or something as concrete as recidivism. Therefore, to address them, we need an approach that acknowledges the constellation of players involved and the roles and actions that they perform. Based on that we can create effective interventions, policy changes and value discussions.Much of the current thinking about how to counter unwanted social outcomes, from youth unemployment to digital inequality, is based on the idea of how start-ups prototype, grow and scale their products.

From 'Using Systems Thinking to Transform Society' by Metabolic, Milieusamenwerking en Afvalverwerking Regio Nijmegen (MARN), Gemeente Nijmegen, ARN BV and Dar NV.

Maker: Maani and Cavana

Download

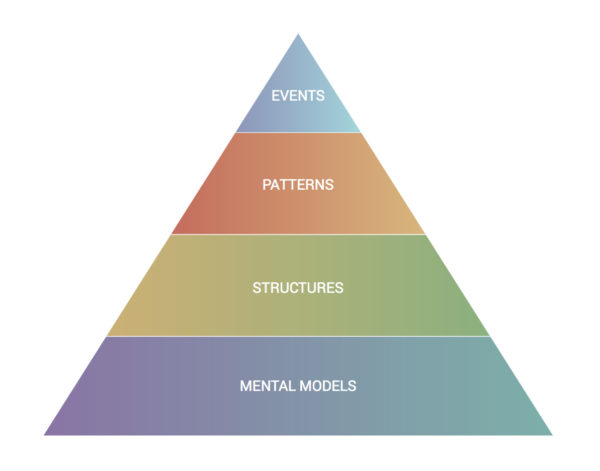

Systems thinking++Systems thinkingSystems thinking has been on Kennisland’s radar in different shapes and forms – visiting scholar Sarah Schulman has conducted research on the concept of systems while she was at Kennisland back in 2013. Read her writing pieces here. acknowledges this dynamic, and provides a suggestion as to how to handle this complexity. As demonstrated by the figure above, the ‘four levels of thinking’ model by Maani and Cavana (2007) indicates how events only make up the tip of the iceberg of systemic problems. An event, for instance, can be the perceived nuisance of unemployed youth in a particular neighbourhood++CorfuplantsoenThis is an example from our own practice. For one of our social lab projects in Amsterdam, we were invited to address the issue – digging deeper, we encountered deeper physical and social patterns that preceded this problem. Read more. Events are sustained by deeper lying patterns, structures, and mental models, which in many social innovation interventions remain unaddressed. By identifying these aspects, actors can start recognising their own roles and foster new relations for different outcomes.

From the Obama Fellowship++Obama FellowshipI spotted on Twitter that the Obama Fellows were using systems thinking methodology – one of the Obama fellows, Kimberly Brown, was kind enough to share their slidedeck with me. to the Ashoka Globalizer, methodologies based on systems thinking are quickly gaining ground and recognition as a way to approach complex social issues. But if 2019 is to be the year in which systems thinking is mainstreamed, three considerations should be at the top of our agenda:

1. Take a look in the mirror

Being born, we are inevitably complicit in the making of this world. As heirs to a society, we inherit the good as well as the bad. This presents us with a responsibility. Exploring your history, privileges and reflecting on the consequences of your actions are essential civic virtues – particularly so, if you count yourself as working towards ‘systems change’. As part of an industry of ‘change makers’, to what extent does your work challenge or in fact even reaffirm the status quo? As part of an industry of ‘change makers’, to what extent does your work challenge or in fact even reaffirm the status quo?

Who are you to change a system?

Claiming that you want to change the system at its least sounds rather presumptuous. Although it might seem evident that something so inherently political as changing social systems cannot be issued by a sole individual, by the risk of being autocratic, accusations of such hubris among social innovators remain few. A whole generation of ‘changemakers’ do not critically reflect on their position, and perceive entitlement to intervene in systems.++ChangemakersFor instance, for a piece I wrote for OneWorld magazine this fall about social entrepreneurs working on an inclusive labour market, the five people I interviewed ended up being a homogenous group of middle-aged white, highly educated Dutch men, who did not seem to consider how their societal position might influence their relationship to their employees. This does not negate their positive social impact per se, but it might spark questions regarding representation and speaking ‘for’ a target group rather than ‘with’.

As argued in the piece Design Thinking Is Fundamentally Conservative and Preserves the Status Quo, Natasha Iskander comments that subjectivity is particularly relevant in cases where innovation projects and data collection rely on how the practitioner or researcher engages with people. For design thinking, social innovation, or any form of ‘co-creation’, the practitioner’s or researcher’s identity and political positioning presuppose what signals are taken into account in the innovation process: in many cases someone leading a social innovation process is de facto elevated to being the creative visionary. So while ‘co-creating’ solutions for elderly care, the use of public space or better education, a disproportionate amount of decision power remains in the hands of ‘the professional’.

Undeniably, my work and decisions are rooted in my identity of being a white, heterosexual, middle class, highly educated woman with politically progressive ideas living in the city of Amsterdam. Undeniably, my work and decisions are rooted in my identity of being a white, heterosexual, middle class, highly educated woman with politically progressive ideas living in the city of Amsterdam. While I might attempt to address blind spots that come with being me, and we shouldn’t cling to the idea that identity is fixed, it is impossible to attain the bird’s eye view. As the saying goes, privilege is invisible to those who have it. Without addressing such imbalances in interventions that aim to change a system, the approach remains hopelessly conservative.

This should, however, not render us unable to act: creating teams that reflect different societal backgrounds, becoming aware of your own position in society++Your own position in societyFor instance by joining an intersectional feminist book club (such as Our Shared Shelf) and following media that dive into these subjects (such as OneWorld). and being transparent about where you applied a subjective ‘filter’ in (design) interventions and where some voices might not have been heard are good starting points.

Saying no to ‘innovation’?

At Kennisland, we observe a trend away from multiple-year government programmes to innovate for social problems. Instead, short-term projects seem to be favoured, which leads to a fragmentation and projectification.++Share your experiencesDoes this resonate with you? Please share your experiences with me at tg@kl.nl. A possible explanation for this could be that since the 2008 recession governments have become more risk averse to investing money for a longer period of time. Such projectification prevents people commissioned from outside governments from getting to underlying patterns and structures (see figure 1).

From personal experience, I have witnessed the constraints of projectification attempt while working with the subsidy desk of the municipality of Amsterdam. Last year, we assisted them in financing and building capacity among small-scale innovative city makers. However, with the ending of our project financing, the subsidy desk changed back to ‘normal’, forgoing the empathetic and tailored approach we spearheaded. As a result, several city makers are at a risk of being swamped in a bureaucratic process possibly having to pay back their subsidies.

If an assignment to innovate for a social problem does not allow for systemic change, will we refuse the job?If an assignment to innovate for a social problem does not allow for systemic change, will we refuse the job? Surely someone else will be willing to lead a ‘design thinking method’ or social innovation module for that particular client. Arguably, what sustains a ‘useful’ project is a subjective matter. But could we unite in a union of change makers, formulating quality standards of commissioned assignments? And if we fail, or disappoint, openly try and understand those failures?

This point is also a call to action to those who commission social innovation. If you, as a civil servant initiate an innovation project or are convinced by an organisation to innovate on a particular issue, can you make a proper judgement call about the thoroughness of an intervention? I invite hubs of innovation, such as our own office at Spring House, as well as civil servants, to critically reflect on how to get there, as well as those designing tenders and commissioning assignments.

2. Link up with movement builders

In the article Neoliberalism has conned us into fighting climate change as individuals, Martin Lukacs argues that obsessing over individual green lifestyle choices deviates valuable time and energy away from an actual societal shift:

“It’s only mass movements that have the power to alter the trajectory of the climate crisis. This requires of us first a resolute mental break from the spell cast by neoliberalism: to stop thinking like individuals.”

In a similar vein, we could argue that individualism has influenced a generation of social innovators who focus on small-scale projectsWe could argue that individualism has influenced a generation of social innovators who focus on small-scale projects. that are not embedded in a more political or systems-change approach. Besides, as argued by Ella Saltmarshe, it’s not enough to draw systems diagrams and approach technocratically: telling stories is a crucial aspect of changing systems. Connecting singular achievements with mass mobilisation is a missing link in social innovation. For instance, despite my own personal efforts of DIY mushroom farming on coffee grounds in my kitchen in an attempt to mimic a circular economy, it took a Zero Waste movement and lobby on a European level to snowball the ban of single-use plastics. Therefore, embedded experimentation and building translocal movements is key.

From isolated to embedded experimentation

Systems are not set in stone: it’s fair to say that your beautiful systems map will probably be outdated next week, or might not even reflect reality in the first place. Only through experimentation can we explore deeper intervention points, and find out how interactions, organisations and feedback loops work.

Going back to the current state of social innovation, we can use systems thinking to prevent what might be called the Beta paradox of experimentation. The Beta paradox++Beta paradoxRead more about this Beta paradox in this article by sociologist Willem Schinkel (Dutch only): Humans as demo. means that experimentation is used to merely optimise or tinker with social services. Progress remains in a constant state of ‘Bèta’The Beta paradox means that experimentation is used to merely optimise or tinker with social services. Progress remains in a constant state of ‘Bèta’.: never finished and therefore never accountable, because we are supposedly always just around the corner of something better. To experiment does not give you a license to set up stand-alone projects, which will turn social innovation into a merry-go-round. Tie consequences to experimentation by using it to map systems, and test alternatives. For instance, what implications do experiments have for legal, financial and accounting structures needed? This specific process of institutional change is what Dark Matter Labs calls the ‘Boring Revolution’++Dark Matter LabsDark Matter Labs is a befriended organisation from the UK: they work on designing institutional infrastructure for a distributed and collaborative future. Treat yourself to this wonderful lecture by founder Indy Johar. : surpassing flashy projects and getting to the meat of institutions.

Besides, experiments should be connected to a movement within an organisation, in which experiment is considered a precondition to change rather than an add-on. Embedding experimentation in a movement within an institution allows for repercussions to happen with regard to patterns, structures and eventually mental models. Failure is also an intrinsic part of experimentation – acknowledge it, learn from it, and encourage people (including civil servants) to be transparent about this. Striking a balance between tying consequences to experiments without killing creativity in institutionalising it, is the million dollar question. Answering it should be part of all social innovation efforts.

Building translocal movements

Bearing in mind that Volkswagen alone has an astounding number of 43 lobbyists++43 lobbyistsThis number is based on the 2015 snapshot performed by LobbyFacts. LobbyFacts is a joint project of Corporate Europe. Read more pushing their interests on our politicians in Brussels, systemic change is not going to happen merely through neatly mapping patterns, structures and mental models. In the outline of his forthcoming book called ‘The Rising – How Movements Are Changing the World For the Better’, Charles Leadbeater argues that social movements are our best bet of driving change across societies in the 21st century. From moving from margin to mainstream, opposition to proposition, to becoming a new norm, Leadbeater sets out a structured account of how movements, such as veganism, change the world.

In the Netherlands different initiatives are popping up to promote fostering social movements.In the Netherlands different initiatives are popping up to promote fostering social movements. CollAction++CollActionCollAction was a finalist for the European Social Innovation Competition 2017, of which Kennisland is one of the core organisers. appeals people to collectively pledge a change in behaviour: from not flying for an entire summer, to not buying new clothes for a year, or collectively switching to a sustainable bank. Furthermore, former Kennisland colleague Jurjen van den Bergh has founded De Goede Zaak (translation: ‘The Good Cause’), whose inception was inspired by Black Lives Matter and the German anti-coal movement. Their website supports people who want to promote a specific progressive civil cause, by providing them with hands-on campaigning support. Of course, the direct action of climate movements and #metoo are other good examples of social movements igniting social change.

But it’s not just the ‘grab your picket sign’ kind of movements that we should connect to systems thinking. As argued by Flor Avelino in Time to ignite the power of translocal social movements, the collective power of grassroots initiatives that locally prefigure alternative practices, systems and futures remains largely untapped. In her piece, as well as during an event I visited featuring the famous scholar Saskia Sassen++Saskia SassenThis event was called Transformative Cities, and was organised by the Transnational Institute. You can watch Sassen’s lecture here. , the conclusion was that local prefiguring efforts need to unite in a transnational social movement in order to counter systemic global crises such as inequality, climate change and the corporate capture of democratic institutions.

Let’s not be naive: social movements are not unequivocally a force for good. What progress means to me, might mean regression to you.Social movements are not unequivocally a force for good. What progress means to me, might mean regression to you. Steve Bannon’s (failing) initiative to unite right-wing extremist political parties in Europe is literally called ‘The Movement’. Besides, having a changing, oblique and self-critical stance is not generally a recipe for success for social movements. Interestingly, the reason that Occupy failed according to many, was their failure to articulate clear demands++The Failure of Occupy Wall StreetHave a look at the article The Failure of Occupy Wall Street (2012) . . When acknowledging that self-criticism is instrumental for achieving better social outcomes (see point one of this article), can a successful social movement have a clear agenda for systems change, while remaining self-critical? If systems thinking is to be linked to social movements, it will need an intersectional approach and concrete links to systems change analysis and practice, to address narratives and value discussions. To find out whether that is a feasible combination will be the next frontier for us to explore.

3. Connect concrete problems to big questions

Bearing in mind the issues of being aware of your position as a professional and the relevance of mobilising collective action for systems change, there remains an obvious omission: how can you consider the issues you work with from a systems perspective? At Kennisland, we aim to pull together (new) consortia of partners in 2019, to apply systems thinking in our projects and emphasise the need for new lasting partnerships and ‘boring revolutions’. If you’re interested to learn more, there is a wealth of literature that you can use to learn about implementing systems thinking, written by people in the field who have learned by trial and error.

Highlights include Wayfinder’s Guide to Systems Transformation, TACSI’s recent report on systems change through practice, this brilliant slide deck by Systems Changers, and David Peter Stroh’s book Systems thinking for social change. In Europe, Metabolic has produced this excellent report Using Systems Thinking to Transform Society, the Stadslab2050 in Antwerp is trailblazing a systems-change approach together with the municipality, and the #RadicalChildcare Systems design lab by ImpactHub Birmingham. If you’re interested in using mapping for systems analysis, check out the Wicked Lab (or their recent webinar), the Systemic Design Toolkit or Societal platform.++Mapping for systems analysisI haven’t used these myself yet so I’d be curious to hear what your impressions are. Also, if you’re interested in creative activism, have a look at this toolkit. If you have really caught the systems bug, you can also join the free Acumen webinar series (but be quick, the course starts on 22 January), as recommended by the instructors of the Obama Fellowship.

Importantly, while these resources help to continuously deepen our understanding of intervening in systems, the underlying ‘big questions’ won’t be solved within a template.While these resources help to continuously deepen our understanding of intervening in systems, the underlying ‘big questions’ won’t be solved within a template. For each social issue that is dealt with in social innovation, be it homelessness, elderly care, or air pollution, a connection needs to be made to the common denominator. Values that are the foundation to the answers of big questions like what it means to live in a democracy, to be a citizen, or even to be human. Such questions lie at the very base of how we deal with issues such as poverty, health, food and the environment. To answer those questions, we need to dig deep. And if you ask me, those answers and the actions that follow might as well present us with the dawn of a new enlightenment.

Triggered by a thought, or curious to connect? Let me know at tg@kl.nl or @Tessa_DG.